Like general partners, the court ruled that the VC firm suing in a California case was involved in DAO management. They might be subject to expensive lawsuits.

Although it is unlikely to be the first thing that comes to mind when considering decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), legal structure is expected to receive increased attention.

It will probably be deemed necessary to have a framework that offers “limited liability” to shield members from fatal claims.

Consider the $70 million venture capital giant Andreessen Horowitz spent on Lido’s (LDO) tokens in 2022.

It came after the cryptocurrency investment company Paradigm Operations bought 100 million LDO tokens in 2021, or 10% of all LDO tokens created. Dragonfly Digital Management, another venture capital firm, also purchased $25 million worth of LDO.

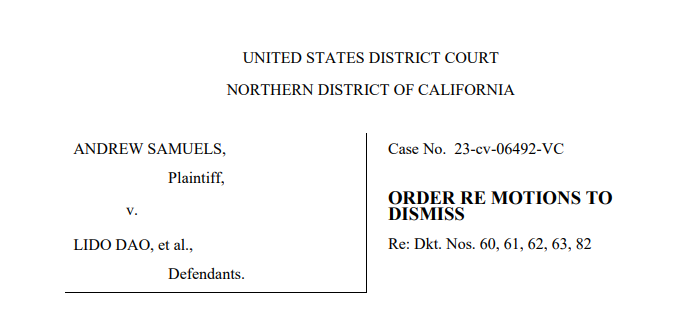

Two years later. On November 18, 2024, a district judge in northern California decided that an investor who lost money on his LDO token investment might file a lawsuit against all three companies. The decision rocked the decentralized autonomous organization community.

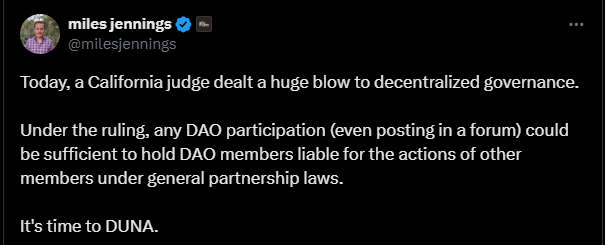

Myles Jennings, general counsel and head of decentralization at a16z Crypto, a venture capital fund founded by Andreessen Horowitz, wrote on social media that a California judge today struck a severe blow to decentralized government. He also added:

A hyperbole? Perhaps not. Although this decision was made in a district court that served the northern portion of one US state, it could have global implications.

VCs participated “actively” in the management of DAOs.

Regarding the decision, Stanford University legal professor Jeff Strnad said, “It’s not surprising, but it is significant.”

According to the Northern District of California court in Samuels v. Lido DAO, the three investment firms “took an active role” in Lido DAO’s management, functioning as general partners. This implied that they might be held accountable for any losses.

Strnad stated that this is “a bad outcome for DAOs.” Without the “limited liability” protection, venture capital firms will not engage in businesses like DAOs.

Kevin Owocki, co-founder of Gitcoin and author of the forthcoming book How to DAO: Mastering the Future of Internet Coordination, said that this decision highlights the increased legal scrutiny of DAOs. “It shows that courts are open to applying novel decentralized structures to traditional legal frameworks—often treating apples and oranges.”

According to Owocki, if the “nuances” of the ruling’s structure aren’t correctly understood, it could impede DAO innovation.

The majority of DAOs need a formal framework.

Thousands of DAOs exist, and they use a wide range of legal frameworks. Corporations, limited liability firms, unincorporated nonprofit associations, and offshore entities are some of the several organizational forms.

However, according to Arina Shulga, a law firm Nelson Mullins lawyer, most DAOs “do not associate with any form of legal entity” at all. She added that these DAOs are unincorporated associations by default since they are general partnerships:

“They still carry legal liability for the actions of their members, and since there is no limited liability shield, the group liability becomes the liability of each individual member of such DAO.”

DAO projects are also global in scope. Although a DAO may have its headquarters in California, its members may reside in Russia. If it is known that VCs like Andreessen are in charge of a company like Lido DAO, a member in Russia may now file a lawsuit against them.

Even for those who are not members, things may become tricky. “You may have a liability issue if you write code, post it to GitHub, and a DAO finds it,” Strnad stated. This kind of activity is a “threat to innovation.”

An effect outside of California

However, this court decision may apply only to California.

“Even though the decision is technically within the Northern District of California’s jurisdiction, it could establish precedent for other US courts, so it’s important to pay attention wherever you are,” Owocki said.

David Kerr, CEO of the advising firm Cowrie, informed Cointelegraph that the actions above did not occur in the United States. Only because some participants resided in California did legal action start there. According to Kerr, the plaintiff chose this court as a good place to file a lawsuit.

For decentralized companies, location might be less critical. “Being nowhere is just a shortcut for being everywhere,” Kerr continued.

Nevertheless, Kerr issued a warning against overreacting to the court’s ruling. Technically, this was merely a move to dismiss a lawsuit. In actuality, the California court did not hold governance stakeholders accountable.

“The court has decided that further investigation is required, so this is just a step to include them in discovery,” Kerr explained.

Do DUNAs have the solution?

“It’s time to DUNA,” the general counsel added in Jennings’ message, which was previously mentioned.

The decentralized unincorporated nonprofit association (DUNA), a new legal organization for DAOs, was established by a statute approved in the US state of Wyoming in March. A DUNA would allow DAOs to do more than only enter into legal agreements with other organizations. Individual DAO members are also given legal protection.

Owocki and Strnad concurred that DUNAs are a suitable remedy for the legal flaws in many DAOs.

However, according to Kerr, the Wyoming DUNA is not a cure-all. “The answer will always be to build solutions around the facts and conditions of a project. The Wyoming DUNA is a tool that can assist in achieving that goal, but like other tools, it may produce a better result if used correctly.

Given that many predict the Trump administration will enact blockchain-friendly legislation this year, does the California court verdict matter?

“A friendlier regulatory and policy regime is probably coming, but it’s not here yet,” Owocki stated.

In the interim, he said, DAO builders should keep pushing for more transparent legislation and ensuring they are in a solid legal and operational position. “DAOs will be resilient due to this focus, irrespective of administrative or policy changes.”

According to Strnad, a favorable cryptocurrency market structure like FIT21 has a “strong possibility” of passing under the Trump administration. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), rather than the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), is granted authority by FIT21.

As with SEC-regulated companies, DAOs would not be required to register or submit quarterly reports if the CFTC were to serve as their regulator. Strnad stated, “But FIT21 has nothing to do with liability.”

“A preventable tragedy”

In conclusion, the California district court decision, part of a continuing legal case, raises a crucial question for all DAO operators and members: Do all players have limited liability? It may still have a limited impact. As Strnad notes, this has nothing to do with problems with market structure.

It’s more about how much money DAO members will be fined if something goes wrong. A fine under limited liability would be about the same as the loss incurred by an investment. However, with limitless liability, which is the kind that venture capital firms might yet encounter in the case of Samuels v. Lido DAO, fines reach $25 million or more.

Regardless, Strnad stated that if you are a DAO, “you better do something to protect yourself from unlimited liability.” “That is a preventable tragedy.”