Following Ghana’s recent implementation of blockchain technology, Mali has introduced AI into its educational system, enabling students unfamiliar with written Bambara to excitedly read novels on ThinkPad computers

Artificial intelligence had created, translated, and illustrated the story on their screens.

An attempt to employ AI to produce children’s books in Bambara and other regional languages is gaining traction. Mali’s relationship with French, the language of its former colonial power, France, has grown more strained. French will still be used in government settings and public schools.

Still, Mali’s military administration last year elevated Bambara and 12 other native languages to the “official” language instead of French due to rising political tensions between the two nations.

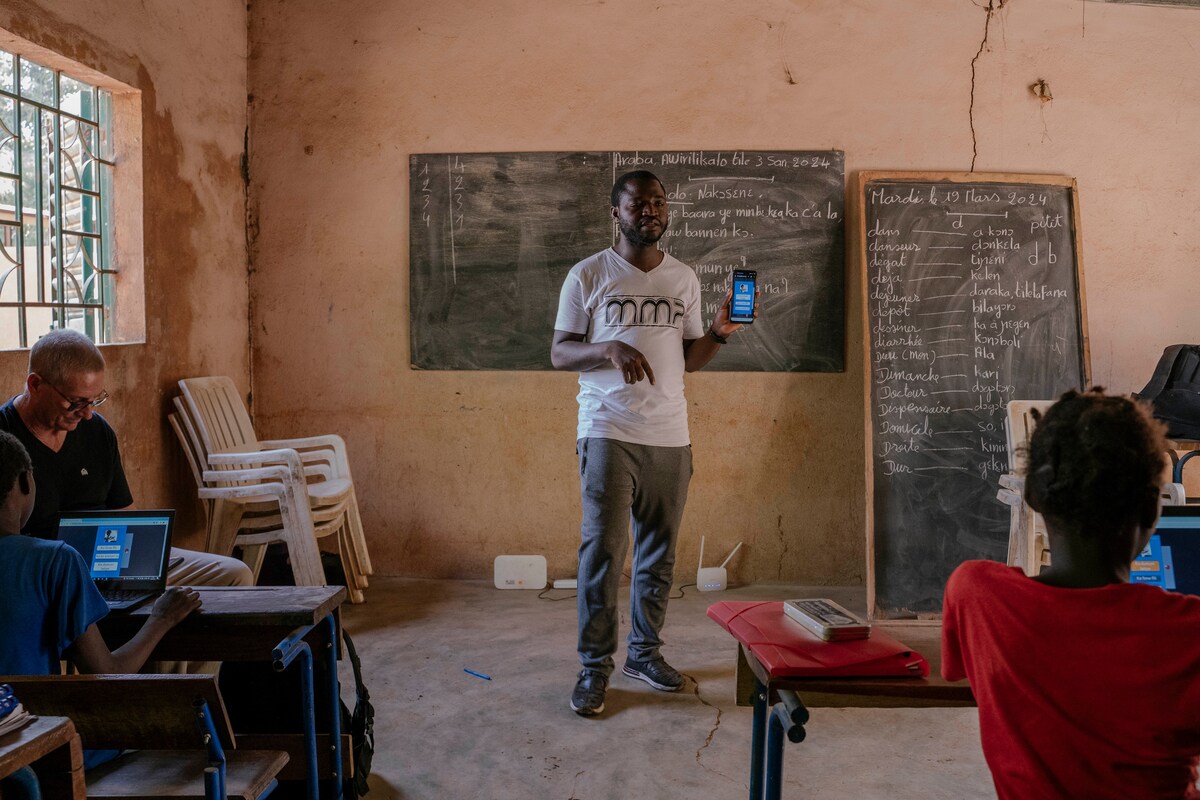

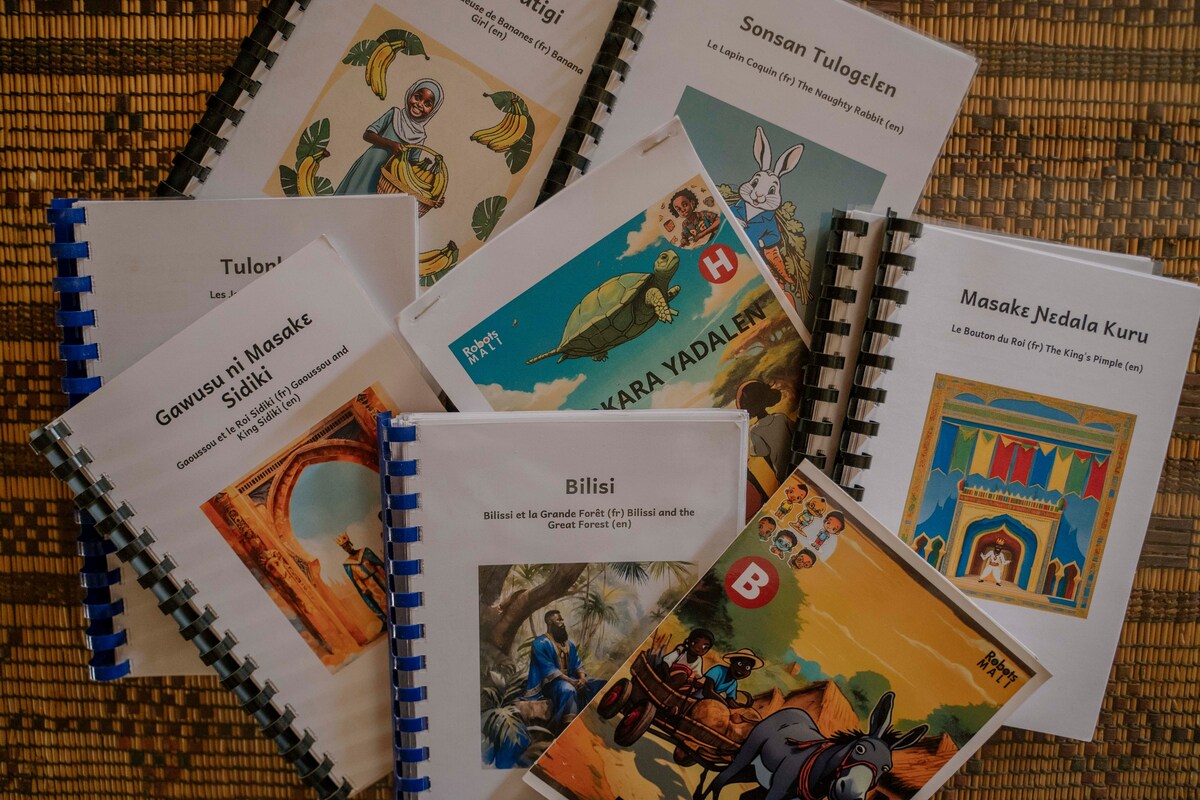

That shift has increased political will behind initiatives. One of them is RobotsMali, a startup that has used artificial intelligence to produce over 140 books in Bambara since last year, according to Séni Tognine, an official in Mali’s Education Ministry who has been assisting RobotsMali in producing its books. He continued that both the government and the people “are engaged in wanting to learn and valorize local languages.”

The lives and customs of common Malians serve as the inspiration for RobotsMali’s stories. Using a cue like “Tell me mischievous things kids do,” RobotsMali’s team transforms a French classic like “Le Petit Prince” into Bambara instead of just translating it.

Using Google Translate, which introduced Bambara in 2022 and utilizes AI to improve its translations, the team—whose work was first published by Rest of the World—eliminates examples that would not apply to most children in Mali.

Then experts like Tognine fix any errors. Another staff member illustrates the narrative using a range of AI picture producers to make the characters relevant to Malian children. She then uses ChatGPT to generate reading comprehension exams.

Twelve pupils who had never attended public school or left it were following along as their teacher read aloud a narrative about things kids shouldn’t do, such as wasting food, picking on their siblings, and speaking back to adults in the Safo classroom. The instructor called on individual pupils to read aloud many times, and they happily did so, occasionally gently correcting one another.

Quiet 10-year-old Soko Coulibaly, who had never attended school, was sitting in the front row and following along with her finger. She said she was “a little scared” when she first saw Bambara written down, wondering, “How am I going to do this?”

After a few sessions, though, she could easily read the words she was so used to saying at home and had begun bringing books back to her mother—one of the seventy percent of Malians who have never learned to read or write.

A problem for languages of Africa

Big generative AI platforms like ChatGPT search websites to help train itself, but most of the nearly 1,000 languages spoken in Africa need to be represented there.

Asmelash Teka Hadgu claimed that ChatGPT generates an absurd tangle of Amharic, Tigrinya, and occasionally even other languages when you ask it the most basic queries in the two most widely spoken languages in Ethiopia, Amharic, and Tigrinya.

Hadgu, who founded a startup that uses machine learning to translate between English and Ethiopian, added that initiatives like RobotsMali demonstrate the promise of artificial intelligence.

“If done right,” he declared, “there is enormous potential to democratize access to education.”

Associate professor Nate Allen of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington said that while China and the US are “undoubtedly at the frontier” of artificial intelligence technology, initiatives like those in Mali demonstrate that “we are living in an era of AI accessibility.”