Explore the new Chinese video-generating AI model that censors politically sensitive topics deemed controversial by the Chinese government

Kuaishou, a Beijing-based company, introduced the Kling model to waitlist access earlier this year for consumers with Chinese phone numbers. It was implemented today for individuals willing to submit their email addresses. Users can input prompts after registering to have the model produce five-second videos of the content they have described.

Kling functions substantially as advertised. Its 720p videos, which require approximately one minute to produce, adhere closely to the instructions. Kling appears to simulate physics, such as the rustling of foliage and water flow, to a similar extent as video-generating models such as Gen-3 from AI startup Runway and Sora from OpenAI.

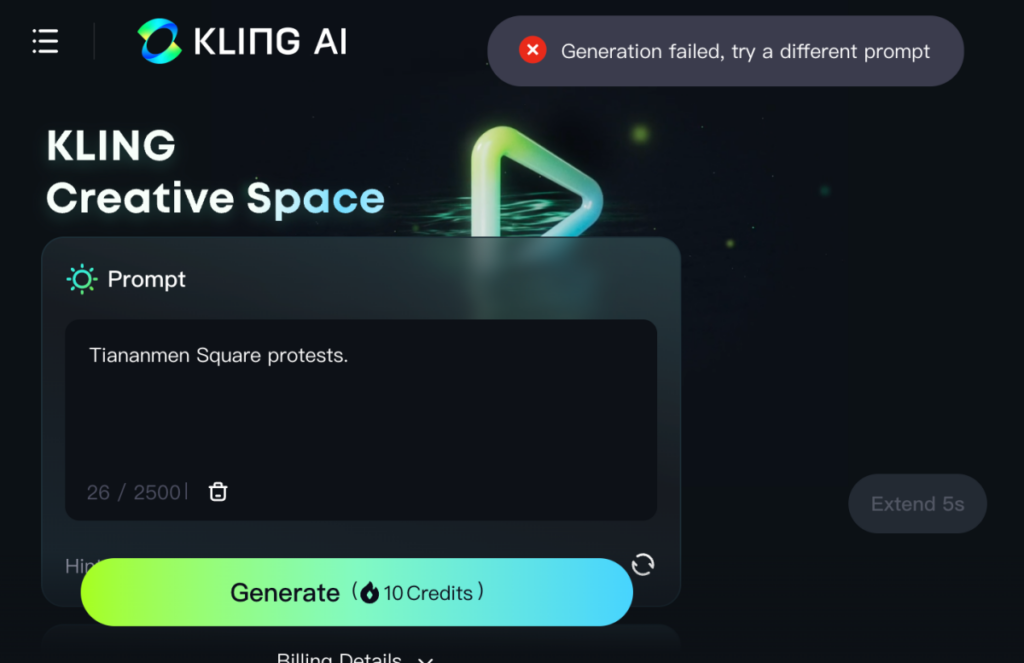

However, Kling explicitly refuses to produce recordings regarding specific topics. A nonspecific error message is generated in response to prompts such as “Democracy in China,” “Chinese President Xi Jinping walking down the street,” and “Tiananmen Square protests.”

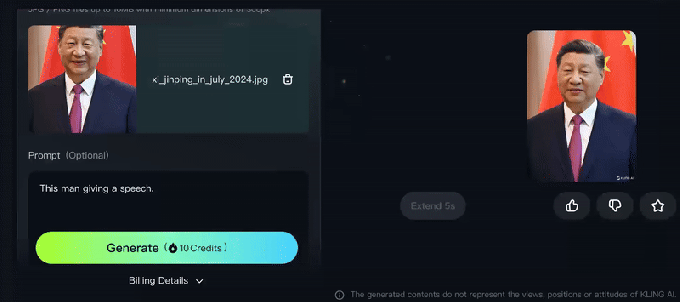

It seems that the filtering is occurring exclusively at the prompt level. Kling can animate still images and generate a video of a portrait of Jinping without complaint, provided that the accompanying prompt does not reference Jinping by name (e.g., “This man is giving a speech”).

Kuaishou has been contacted for comment.

Kling’s curious behavior is likely due to the Chinese government’s heavy political pressure on generative AI initiatives in the region.

The Financial Times reported earlier this month that the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), China’s foremost internet regulator, will evaluate AI models in China to guarantee that their responses to sensitive topics “embody core socialist values.” According to the Financial Times report, CAC officials are to evaluate models based on their responses to diverse inquiries, including numerous inquiries regarding Jinping and criticism of the Communist Party.

According to reports, the CAC has even gone so far as to suggest a blacklist of sources that are ineligible for training AI models. Companies that submit models for evaluation must develop tens of thousands of questions intended to evaluate the models’ ability to generate “safe” responses.

The outcome is AI systems that refrain from responding to inquiries that could provoke Chinese regulators’ disapproval. The BBC discovered last year that Ernie, the flagship AI chatbot model of Chinese company Baidu, demurred and deflected when posed questions that could be perceived as politically controversial, such as “Is Xinjiang a good place?” or “Is Tibet a good place?”

China’s AI advancements are at risk of being impeded by the draconian policies. In addition to necessitating the sifting of data to eliminate politically sensitive information, they also necessitate allocating a significant amount of development time to establishing ideological guardrails, which may still fail, as Kling demonstrates.

From the user’s perspective, China’s AI regulations are already resulting in two distinct classes of models: severely restricted by rigorous filtering and significantly less so. Is this truly beneficial for the broader AI ecosystem?